(This write-up is identical to the article with the same title found on pages 1-34 of the book entitled "The Filipino Tragedy and Other Historical Facts Every Filipino Should Know," published by the author. The sources and references indicated here are contained on pages 402-415 of the book.)

Abstract

The Filipino-American war resulted not only in

the conquest of the Philippine Islands by the United States but also ushered in

the transformation of the Filipino from the patriotic to the servile, whose

descendants today are grappling with national identity and damaged culture.

Deception, mockery, and atrocities marked the conduct of the war waged by U.S.

President William McKinley to put the Philippines on the map of the United

States. This McKinley misadventure was destined to be an ugly blot in the

glorious pages of American democratic heritage had it not been for the

deliberate efforts to minimize, if not eliminate, the memory of the war through

deliberate dissimulation and re-education. The subterfuge created a new Filipino

bereft of history and demonstrable national identity. Undeniably, the American

conquest of the Philippine Islands was a case of subjugating an unwilling

people and making the same people forget they were subjugated. This is the Filipino tragedy. The need of today is to reclaim the patriotic

character of the chaotic past and use it to inspire and guide efforts toward

the path to national liberation that will uplift the Filipino people from

ignorance, apathy, and poverty.

Introduction

It is truly a puzzle that Filipinos do not have the kind of

patriotism of the Japanese or the Koreans. Yet, two decades and a hundred years

ago, this country teemed with heroes who carried out a successful revolution

against Spain and resisted the powerful army of the United States to defend

their newly-born republic. Men like Maximo Abad, Crispulo Aguinaldo, Eugenio Daza, Martin Delgado, Ananias Diokno,

Edilberto Evangelista, David Fagen,

Faustino Guillermo, Ambrosio Flores, Urbano Lacuna, Sixto Lopez, Arcadio

Maxilon, Julian Montalan, Simeon Ola, Luciano San Miguel, Julian Santos, Manuel

Sityar, Jose Tagle, Candido Tirona, Flaviano Yenko (to name a few of the

unheralded) sacrificed their lives and or their properties before the altar of

freedom and liberty.

But today, ineptitude, helplessness, indifference, and disregard for law and order prevail. Seekers of favor, privilege, and position outnumber those who are willing to make sacrifices for the country. Those elected or appointed to positions in government had in the past used their talents and experience to enrich themselves instead of doing what was good for the country. And not one among contemporary public officials shows any real interest in leading the people out of poverty, ignorance, and apathy. The puzzle becomes even more pronounced when the question is asked why the likes of Rizal, Bonifacio, Jacinto, Del Pilar, Luna, Lopez Jaena, Ponce, or Aguinaldo are nowhere to be found. Is something hidden in the past that is still unknown to most Filipinos today?

Revisiting the Aguinaldo Era

A diligent student of Philippine history could use the internet to get to the facts that would lead to the solution of the puzzle much faster. With some luck, he might find himself in a gold mine of information - books, pamphlets, and documents containing unfamiliar accounts and events, facts not taught to Filipino students in schools. Indeed, so much had been deliberately left out to the present day in Philippine school textbooks concerning the events that took place after the United States succeeded Spain as the colonial master of these islands at the turn of the twentieth century.

It will take a little while to gather the data and digest the facts, but eventually, a straightforward scenario will form in one's mind like several frames, as in a graphical presentation. First to show would be the frame of Bonifacio, then Aguinaldo, then the battle of Manila Bay, then the Filipino revolutionary army, then the siege of Spanish garrisons throughout Luzon, Visayas, and parts of Mindanao, then the victorious Philippine national flag flying in towns and cities, then the first Philippine Republic, then the Filipino-American war, then the American colonial government, then the public school system and the final frame, the new Filipino.

The student would soon realize that the reason why today's generation of Filipinos are less patriotic is that they are descendants of the new Filipinos or those that William Howard Taft called the little brown brothers (Taft, 125). These were the generation of Filipinos who had undergone re-education, a process which the nationalist historian, Renato Constantino, referred to as the remaking of the Filipino. The parents were patriotic Filipinos who fought side by side with Aguinaldo, but the offspring would be taught to become subservient Filipinos of the American colonial era.

But what would likely escape notice by the unwary student is that the re-education process was not accidental, or a result of teaching English or other American-oriented subjects. As will be proved later, the re-education process was deliberate. It was carefully designed to erase from the memory of the Filipinos a very sad chapter in their country's history. The public school system was utilized to implement a systematic process of indoctrination in order that Filipinos will have no recollection of the horrors they went through in their heroic resistance to American occupation. That the process was successful can be gleaned from its product, the new Filipino, whose descendants today are wrestling with lost national identity, unfamiliar with the blood and tears that their forefathers shed in a bitter struggle to establish a government of their own, free and independent.

Mckinley's Clever Ploy

The story of the transformation of the Filipino from the patriotic to the subservient came about with the rise of America as a world power in the late 19th century. U.S. President William McKinley wanted to take the Philippine Islands as an American colony following the British model. However, a territorial expansion that ignored the rights of the inhabitants to American citizenship violated the constitution of the United States and the libertarian tradition of the American people. Nevertheless, McKinley took the path of the expansionism. He did not give credence to the favorable opinion of Admiral Dewey and the other American generals that the Filipinos were capable of self-government.

He also refused to acknowledge the accomplishment of the Filipinos in defeating the Spaniards and establishing a de facto government that controlled most of the country and administered to the native population. The so-called Filipino republic, according to Washington officials, was not recognized as a belligerent by foreign powers, e.g., England, France, Germany, Japan, or Russia, and therefore, for practical purposes, did not exist. But whenever the American generals needed anything from Aguinaldo - horses, wagons and carabaos, timber, encampments, supplies, or information, he was addressed as Senor Don Emilio Aguinaldo, General, Commanding Philippine Forces (Leonidas, 95).

Rather than sympathize with a struggling people, the McKinley administration concocted a clever ploy. The American public was made to believe that the Filipinos were savages, uncivilized, and unfit for self-government. The Filipinos were likened to the American Indians, who lived among several tribes scattered all across the Philippine archipelago. McKinley presented himself as the knight in shining armor that Divine Providence had anointed to lead the Filipinos out into the bright sunlight of western civilization. (Storey and Lichauco, 177).

[Author’s note: Tribesmen from the Philippines, primarily

Igorots, were brought to the United States and displayed at fairs and

expositions in several cities. Its

purpose was unclear, but the result solidified McKinley’s claim that Filipinos

were savages and unfit for self-government. It softened American public

resistance to his adventure into imperialism, masquerading as a humanitarian

mission of uplifting and preparing the Filipinos for self-government.]

But General Charles King, who fought the Filipinos, had a contrary opinion. He said:

"The capability of the Filipinos for self-government cannot be doubted; such men as Arellano, Aguinaldo, and many others whom I might name, are highly educated; nine-tenths of the people read and write; all are skilled artisans in one way or another; they are industrious, frugal, temperate, and, given a fair start, could look out for themselves infinitely better than our people imagine. In my opinion, they rank far higher than the Cubans or the uneducated negroes to whom we have given the right of suffrage." (Leonidas, 129-130).

McKinley ignored the fact that there already existed a mass of Filipino intelligentsia composed of propagandists who obtained their education from Europe and together with the island's educated

Ilustrados, they took an active part in the revolution and collaborated with President Emilio Aguinaldo in administering a government that was formed under a republic established after 300 years of Spanish rule.

The attraction of the Philippines to McKinley must have been the prospects of enormous profits from hemp, sugar, timber, Indian rubber, gold, silver, and other precious metals, coaling stations, and control of commerce in the east that made the Wall Street schemers very excited, who gave their wholehearted support to McKinley's imperialistic adventure. But the American public was not told that the Filipinos fought the Spaniards to gain their independence and would fight the Americans to defend that independence. And so McKinley was able to wiggle out of the constitutional restraints and proceeded to annex the Philippines, encouraged by the ayes of the members of the United States Congress and applause of the American people. But apparently, the motivations behind the annexation of the Philippines by the United States were not entirely anchored on territorial expansion or commercial benefits. England played a part in the decision of the United States to keep the Philippines, viz:

“About the early part of June 1898, the English papers began to publish articles urging the Americans to keep the Philippines. England became alarmed at the prospect of a republic being set up in the Orient. It would be like starting a prairie fire among her Malay subjects in Borneo, Singapore, Hongkong, and her other East India possessions. Hence President McKinley did not wish to start another Paul Kruger to set a bad example to the subjects of the Empress of India. The ‘London Spectator', on the Philippines, hoped the United States would keep them, saying: 'The weary Titan needs an ally, and the only ally whose aspirations, ideas, and language are like his own is the great American people." (Pettigrew, 607)

The Betrayal

When news came that Dewey's fleet was sailing to the Philippines, the Spaniards, in preparation for the looming conflict with the Americans, formed an alliance with the former leaders of the revolution, who had returned from the field as a consequence of the Peace Agreement of Biak-na-Bato. But as soon as Aguinaldo arrived from Hongkong in May 1898 aboard the American gunboat, the McCullough, he rejected the alliance with Spaniards saying it was too late because he had already agreed to join forces with the Americans.

Aguinaldo raised an

army of forty thousand which he armed with rifles purchased from Hong Kong with

the Biak-na-Bato money and also with arms captured from Spanish

forces. He defeated the Spanish army and drove the remnants into their

last stronghold, the Intramuros in Manila.

The victorious feat

of Aguinaldo did not escape the notice of the Americans. General Thomas

Anderson made this comment:

"At that time [July, 1898] the insurgent Filipinos

had driven the Spanish soldiers within the defences of Manila, and had them

completely invested on the land side by light field works, which they held with

about fourteen thousand men. They were poorly armed and equipped, yet, as they

had defeated the Spaniards in a number of fights in the field, and had taken

four thousand prisoners , it

may be asserted in the vernacular of the camp that they ' had the morale on

them.' The Manila garrison was so demoralized at that time and so incomplete

was their line of defence that I believe it would have been possible, by coming

to an understanding with Aguinaldo, to have carried their advance works by

storm and to have captured all of the city, except the walled city or the old

Spanish town." (Philippine Information Society[1.2], 7)

"One by one, Spanish

garrisons yielded, increasing the revolutionary army’s members and war

equipment. Perhaps not surprisingly, scattered Spanish garrisons put up

hardly more than token resistance. Several troops fled – when this was

possible. For example, General Monet fled from Pampanga and Enrique Polo de

Lara abandoned Ilocos, Admiral Peral cut off 800 men adrift on Manila Bay lest

his flight be slowed down. The tragedy of all this lay in the fact that,

within a few months between 8,000 to 9,000 Spanish soldiers, government officials,

and friars fell into the hands of hostile Filipino rebels. Perhaps, had

they forseen the length and hardship of their captivity, the Spaniards might

have put up a more determined resistance. As it was, the rank and file of

the Spanish colonial forces paid a high price for their leader’s mediocrity and

self-interest." (Arcilla, 128)

An American observer believed that it would have been difficult for the Americans to fight the Spaniards in the Philippines if they succeeded in joining forces with the Filipinos, viz:

"Had Consul Wildman, Consul Pratt, and Admiral Dewey remained dumb to the entreaties of the banished Insurgent chieftains and Aguinaldo, they would have been weaned back by Spain, and the American flag would not be floating over the Philippines today; for we should not have attempted to fight Spain on Philippine soil had the Filipinos joined forces with their former masters." (Wildman, 67)

A similar prognostication was expressed by Captain J. Y. Blunt, an American officer who served in the Fifteenth Cavalry in 1901 and later as a member of the Philippine Constabulary, and author of the book, "An Army Officer's Philippine Studies," viz:

"Had the Filipino leaders ,.. become convinced that their idea about the Americans was erroneous, such conviction might possibly have caused them to accept ... the overtures of autonomy extended by the Spanish authorities. ... Backed up by the Spanish forces, they (Filipinos - author) could have offered resistance to any force he (General Anderson - author) might have attempted to use and the Americans might have become the 'common enemy' with himself exposed to a possible defeat in the field." (Blunt, 172-173)

But

Aguinaldo was true to this word and took his agreement with the Americans as an

obligation. Soon after his arrival, a

mixed commission of citizens saw him offering autonomy. The commission believed that General Agustin

and Archbishop Nozaleda would recognize his rank of General and that of his

companions and would give him a $1,000,000 indemnity agreed upon at

Biak-na-bato still unpaid, as well as liberal rewards for and salaries to the

members of a popular Assembly (Aguinaldo[True Version], 34). Aguinaldo rejected the offer.

[Author’s note: At the height of the Filipino-American War, Aguinaldo received a similar bribe offer from

the Schurman Commission of a yearly bonus of $5,000 and leadership of the Tagalogs and authority to

select from his men those who would occupy minor municipal positions in exchange for the restoration

of peace under American Administration. Aguinaldo rejected the offer and insisted upon immediate self�government. (Van Meter 151-152)]

Soon after Aguinaldo had proclaimed Philippine independence,

large contingents of American troops started to arrive, whose number stood at 11,000 by end of July 1898.

These American troop arrivals raised concerns among Aguinaldo's generals. Still, Aguinaldo kept his faith in the promises of Dewey and the other American officials, who must have impressed on Aguinaldo the belief that the Americans would respect Philippine independence. He continued to keep the pressure on the Spaniards by controlling the water supply and the entry of provisions into the city.

Aguinaldo's plan was not to bombard or attack the city but to starve it into submission (The Strait Budget newspaper article - "At Manila"), a tactic he successfully employed during the earlier Cavite campaign. The Spaniards were forced to survive on horse meat and rainwater and ultimately capitulated, but not to Aguinaldo, whose demand the Spaniards ignored. Instead, the Spaniards handed the city over to the Americans on August 13, 1898, after a few shells were fired and minor skirmishes began in what is called the "mock battle of Manila" (Van Meter, 233).

Unknown to Aguinaldo, the negotiations between the Americans and the Spaniards for the capitulation of the city were already concluded back on July 24th through the intermediation of the Belgian Consul, Edward Andre, for the purpose of avoiding a conflict and preventing the bombardment of the city or its capture by the Filipinos (Van Meter, 231). The minimal exchange of fire was intended to save the honor of the Spanish military (Blunt, 166-167; Elliott, 307-308). In effect, the ultimate prize of the Philippine revolution, the victory over Spain, was deliberately denied to the Filipinos because it would have been catastrophic to the honor of Spain if she surrendered to her former subjects.

The Filipinos were not invited to participate in the capture of the city because President McKinley had instructions that there should be no joint occupation with the Filipinos. But nonetheless, Aguinaldo launched a simultaneous attack from several points and occupied practically the fringes of the city - Tondo, Sampaloc, Paco, Malate, Ermita, and Luneta, only to be barred by the Americans from entering the innermost section, the Intramuros.

The resulting tense situation almost erupted into a shooting war had it not been for the intercession of Generals Ricarte and Noriel, and General Anderson on the American side. The Filipinos expressed anger and indignation, saying they considered the war their war, Manila as their capital, and Luzon as their country (Van Meter, 235).

Having been informed by the Americans that there should only be one Army

in the city at one time, Aguinaldo was served notice by General Otis that "…

unless your troops are withdrawn beyond the line of city defenses before

Thursday, the 15th instant …", the demarcation line as defined in the Peace

Protocol signed on August 12, 1898, in Washington DC between Spain and the

United States, he (Otis) shall be obliged to resort to forcible action (Pettigrew,

212). And before the expiration of the ultimatum given by Otis, the Filipino

Republican Army marched out of the city on September 15 to positions beyond

the city limits (Stickney, 293-297).

The so-called mock battle of Manila and the surrender of the city would have been unnecessary because the Peace Protocol gave the Americans the right to hold the city, the bay, and the harbor, pending the disposition of the status of the Philippine Islands (Blount, 121). However, the time difference and the delay in the transmittal of news rendered it irrelevant.

Meanwhile, the determination of the disposition of the Philippines, as provided in the Peace Protocol, was being negotiated in Paris. Experts from all over the world were asked to testify before the peace commissioners, but not one Filipino was invited to speak. Both the United States and Spain ignored the Filipinos' request to participate in the conference. Aguinaldo's handpicked representative, Felipe Agoncillo, went all the way to Washington D.C. to seek President McKinley's recognition of the Philippine Republic and secure credentials to allow him (Agoncillo) to take part in the peace negotiations, but his representation was not recognized, neither was his Memorial to the U.S. Senate, justifying Philippine Independence, officially received by McKinley or the State Department. Failing to get American support, Agoncillo went to Paris, but similarly, he was not accorded due recognition and was prevented from attending the meetings.

According to Mabini, this treaty that ceded the Philippines to the United States was completely void because Spanish dominion over the Philippines had ceased with the triumph of Filipino arms, and the exclusion of the Filipinos from the treaty negotiations violated international law and the natural divine rights of Filipinos to whom belongs the sovereignty of the islands (Taylor[IV], 67). The Spanish authority in the islands had ceased after Manila, the seat of the Spanish government, was surrendered to the Americans. While the Americans held the city of Manila, the Filipinos were in control of the country. If there were any negotiations about the future of the islands, it should have been between the Americans and the Filipinos.

The Outbreak of War

After the signing of the Treaty of Paris on December 10, 1898, but before ratification by the U.S. Senate, McKinley issued his benevolent assimilation proclamation extending U.S. sovereignty over the whole of the archipelago. This Filipinos protested this proclamation to no avail. Shortly after that, the arrival of more American troops swelled the number to 22,000 by end of 1898, General Otis commenced the war on February 4, 1899 (Sheridan, 170-172).

"While I, the Government, the Congress and the entire populace were awaiting the arrival of such a greatly desired reply (to the proposal for U.S. recognition of Philippine independence under a protectorate), many fairly overflowing with pleasant thoughts, there came the fatal day of the 4th February, during the night of which day the American forces suddenly attacked all our lines, which were in fact at the time almost deserted, because being Saturday, the day before a regular feast day, our Generals and some of the most prominent officers had obtained leave to pass the Sabbath with their respective families. General Pantaleon Garcia was the only one who at such a critical moment was at his post in Maypajo, north of Manila, Generals Noriel, Rizal and Ricarte and Colonels San Miguel, Cailles and others being away enjoying their leave. " (Aguinaldo, 51)

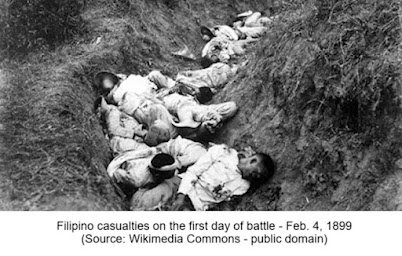

The attack dealt a crushing blow to the Filipino army, that suffered 4,000 dead and wounded against American losses of 175 after a day of fighting (Foreman, 487). Gen. Otis reported the results of the first day of battle as follows:

"Our losses for the day in killed and wounded numbered about 250. Those of the enemy will never be known. Our hospitals were filled with their wounded, our prisons with their captured, and we buried 700 of them. Their loss was estimated at 3,000, and, considering the number who died on the field of battle, might be deemed conservative." (Van Meter, 330)

[Author’s note: The month of February also saw General Luna lead 6,000 Filipino troops to an unsuccessful

counteroffensive to take Manila, leaving behind many casualties.]

The heavy Filipino loss needed the iron hand of General Antonio Luna, who was commissioned by President Aguinaldo four months before, to regroup, reorganize and revitalize the Filipino Army. (The month of February also saw General Luna lead 6,000 Filipino troops to an unsuccessful counteroffensive to take Manila, leaving behind many casualties.) The Americans placed the blame on the Filipinos for allegedly attempting to cross American lines, while the Filipinos accused the Americans of extending their lines a mile beyond the city limits.

The day following the outbreak, Aguinaldo offered a ceasefire and a neutral zone to separate the two armies pending resolution of the conflict. General Otis rejected the offer saying,

"...fighting having once begun must go on to the grim end." (Philippine Information Society, 1.6:38;

Pettigrew, 198

), This inflexible position of General Otis betrayed the true motives of the Americans and reflected the imperialist policy of McKinley when he said:

"The insurgents struck the first blow. They reciprocated our kindness with cruelty, our mercy with Mausers ... There will be no useless parley until the insurrection is suppressed and American authority acknowledged and established. The Philippines are ours as much as Louisiana, by purchase, or Texas, or Alaska." (Sawyer, 120).

McKinley used the news of the outbreak of the conflict to make the Filipinos appear as aggressors and influence a wavering U.S. Congress to ratify the Treaty of Paris by a majority of only two votes. This development sealed the fate of Philippine independence and signaled the imminent downfall of the first Philippine Republic.

Resisting American Occupation

McKinley's benevolent assimilation proclamation gave the Filipinos only one choice - submit to American authority or die. The Filipinos chose the latter - fight a vastly superior army rather than submit to a new master.

The belligerent reaction of the Filipinos to the American imposition was justified by Col. James Russell Codman, viz:

"It

is an undeniable fact, proved by unquestionable evidence, accessible

to any citizen who will take the pains to obtain it, that Aguinaldo's

assistance in the war with Spain was solicited by United States

officials; that he and his friends were used as allies by the

American naval and military commanders; that, until after the capture

of Manila, to which they contributed, they were allowed to believe

that the independence of the Philippine Islands would be recognized

by the American government; and that it was not until after the

American forces in the islands had been made strong enough to be able

- as was supposed - to conquer the Islanders, that the mask was

thrown off. Independence was then refused them, and the purpose of

the president to extend the sovereignty of the United States over

them by military force was openly proclaimed. That the Filipinos

resisted, and that they took up arms against foreign rule, was

something that ought to have been expected; for it is exactly what

Americans would have done." (Codman,

1)

For almost a year, the Filipino Republican Army faced the powerful American Army in open-field or conventional warfare, only to be routed in every engagement. Filipino initiatives for a truce were rebuffed by the Americans with a demand for an unconditional surrender of the entire Filipino Army before any talks were opened. But the Filipinos refused an unconditional surrender without a clear commitment that a Filipino government under an American protectorate would be respected. So, the fighting went on.

The succession of defeats on various battlefields forced Aguinaldo to retreat to the north. And from the last line of defense at Bayambang, Pangasinan, the Filipino generals held a council of war on November 11, 1899, and recommended to Aguinaldo a shift to guerrilla warfare. Accordingly, Aguinaldo issued an order to disband the 30,000-strong Filipino Republican Army and constitute the officers and soldiers into guerrilla units of their respective provinces.

The Guerrilla Warfare

The shift to guerrilla warfare surprised the Americans, who began to suffer heavier casualties from sneak attacks and ambuscades by Filipino guerrillas. This unique mode of warfare not only required armed able-bodied fighting men but more importantly, the active participation of the civilian population, viz:

"The guerrillas only fought when victory seemed a certainty, and most engagements took place between small, isolated American units and well-informed guerrillas occupying ambush positions in situations calculated to place the Americans at a disadvantage. The guerrilla system of espionage, the shadow governments operating behind the scenes in the municipalities, and the reign of terror in the towns and villages all worked to the advantage of the guerrillas and kept the American garrisons completely in the dark concerning guerrilla plans, movements, and strength. Americans found themselves besieged in their own garrisons, and in some regions, it was considered unsafe to go forth in units of less than forty or fifty men. After an attack, the revolutionary forces assumed civilian garb and concealed themselves among the peaceful inhabitants of the towns and barrios. American soldiers could never be sure just who was an active revolutionary and who might be a potential friend." (Gates, 171)

An American officer wrote this to his mother:

"It has occurred several times when a small force stops in a village to rest the people all greet you with kindly expressions while the same men slip away go out into bushes, get their rifles and waylay you further down the road. You rout them and scatter them they hide their guns and take back to their houses and claims to be amigos. " (Gates, 172)

And this item from Brigadier General Frederick Grant:

"I

had two companies of the 32d Regiment of United States Infantry

stationed at the town of Dinalupijan (Dinalupihan),

an important place, as it was located some little distance back from

the coast at the entrance of a pass over the Zambales Mountains. The

natives here seemed to be very friendly and fraternized with our

troops. It was the custom every ten days to send a wagon from

Dinalupijan with a small detachment to the town of Orien (Orani)

for supplies. Of course the natives soon learned of the strength and

travel of this escort, and one day when it passed down to Orien they

broke down a culvert on the road, so that when the loaded wagon came

back its wheel went through the culvert with a jolt and the soldiers

collected around to raise the wheel out of the hole. While they were

thus bunched together, the insurgents, who were hidden in bamboo

bushes, not more than forty to fifty yards away, fired a volley into

them. Six of the eleven United States soldiers fell dead or mortally

wounded; the other five jumped across the road and succeeded in

holding the insurgents off, and worked their way back to Orien."

(Grant,

8)

A Washington paper published this report, viz:

”Dispatches from Manila

stating that more troops are needed and that the American army is

suffering embarrassment and unnecessary losses on account of the lack

of a sufficient force to occupy the territory from which the

insurgents are driven, attract much attention here. “

(Swift, 257)

And from an American officer

”Much of the news sent home by correspondents is so shamefully false that it does our cause great injury among the foreign interests here. Gen. Otis keeps sending reports that the insurrection will soon be suppressed. Nobody in the field believes such stuff. The insurgents can fight a guerrilla warfare with 10,000 men, such as will keep 100,000 American troops busy for five years. In the rainy season, all campaigning on a large scale must stop. Meantime the insurgents can recuperate, replenish their supplies of ammunition, go on cultivating their fields in the interior and suffer comparatively little hardship. “ (Swift, 261)

So the bloody conflict, the first modern guerrilla warfare in Asia, dragged on for three more years. The tenacity of the Filipinos was reflected in a statement of Teodoro Sandico, a member of the Aguinaldo cabinet, who issued a proclamation on May 16, 1899, which said in part:

“Before

accepting autonomy (which we shall do only as a last resort) I think

it is our duty to exhaust all our resources for war, organize all our

forces, and not consider ourselves conquered until the last cartridge

has been fired.” (Philippine Information Society, 1.7:21; Taylor[IV],639; Philippine Information Society[1:7], 21)

A prolonged war was not favorable to McKinley who was facing a 1900 reelection bid. Neither was he willing to let the American public know exactly what was going on in the Philippine islands. He refused to acknowledge the opinion of General Arthur MacArthur (who replaced General Otis) that the whole Filipino nation was loyal to Aguinaldo (Blount, 24) and that practically every town served as a base of Filipino guerrilla operation with full moral and material support from the townspeople (Gates, 195).

"When I first started in against these rebels", said MacArthur, "I believed Aguinaldo's troops represented only a fraction. I did not like to believe that the whole population of Luzon – the native population, that is - is opposed to us and our offers of aid and good government. But after having come this far, and having been brought much into contact with both insurrectos and amigos, I have been reluctantly compelled to believe that the Filipino masses are loyal and devoted to Aguinaldo and the government he heads." (Van Meter, 366-367)

McKinley was following a very clear objective – put the Philippines on the map of the United States. Therefore, he had to misrepresent to the American people that the war was being waged only by a band of rebels that he referred to as the Tagalog tribe and that several other tribes were willing to accept American authority. He had to keep the American public holding on to the misconception that the Filipinos were savages in the same league as the American Indians, unfit to govern themselves, and therefore, justify his intervention and impose his program of benevolent assimilation.

This active insurrection 10,000 miles away that called for the deployment of more troops was a definite political disadvantage to McKinley. But as the war raged, the American public could not understand why a small band of savage Tagalog tribes was able to resist the most powerful army in the world, with 70,000 soldiers manning 500 stations by June 1900 (Storey and Lichauco, 160). The politics and the unusually stiff resistance put up by the Filipino guerrillas placed the American generals under severe pressure to end the war soonest. It was under these conditions that MacArthur saw through the situation and came up with a new campaign strategy, viz:

"...the new pacification effort was based on his strong opinion that one of the most effective means of prolonging the struggle now left in the hands of the insurgent leaders is the organized system by which supplies and information are sent to them from occupied towns. The objective of the campaign was to interrupt and, if possible, completely destroy this system." (Gates, 206)

This conclusion was evident from a field report of an American officer:

"The revolutionaries, not the Americans, controlled the towns and villages. In the town of San Fernando, for example, not only were local officials collecting contributions for the revolution, but they had given the town treasury to the guerrillas. They were also communicating with other towns and planning ways in which to resist the Americans. All of this happened in a municipality garrisoned by American troops. In San Juan, the president falsely translated information given by a young boy and prevented the capture of guerrillas close to an American patrol. In another town, money given the guerrillas from the town treasury was hidden under the entry of 'public improvements'. General MacArthur called Johnston's report 'the best description which has reached these headquarters of the insurgent method of organizing and maintaining a guerrilla force.'" (Gates, 195)

MacArthur's new strategy involved the

“cutting off of the income and food of insurgents, and by crowding them so persistently with operations as to wear them out" (Ramsey, 7).

The implementation of the new campaign strategy was clearly expressed in circular order no.22 issued by U.S. Brigadier General Franklin Bell:

"To combat such a population, it is

necessary to make the state of war as insupportable as possible, and

there is no more efficacious way of accomplishing this than by

keeping the minds of the people in such a state of anxiety and

apprehension that living under conditions will soon become

unbearable." (Storey and

Lichauco, 120).

In short, the target of the new military campaign shifted to the civilian population who were made to suffer in order to force them to desire peace and deny support to the guerrillas. And it was at this point when the norms of civilized warfare were selectively applied and strict press censorship enforced.

The Atrocious War

"By the middle of 1900, Americans and Macabebes resorted to water torture and other forms of terror. They seized people and forcibly filled their stomachs with water until they revealed the hiding place of guerrillas, supplies, or arms." (Gates, 175)

Water cure, or waterboarding as the term is use in American parlance in our generation today, was practically the only way the Americans could get a Filipino to betray his countrymen (Blount, 204). There was no room for neutrals. Every inhabitant should either be an active friend or be classed as an enemy (Ramsey, 49).

The

Reconcentrado, or the Spanish method of separating combatants, was extensively used. Civilians were herded into a town designated as a security zone and any person, animal, food, or anything useful to the guerrillas found outside the security zone were either killed or destroyed.

General Bell, in his report of December 6, 1901, to Washington disclosed the methods he employed to rid Batangas of rebels, viz:

"I

am now assembling in the neighborhood of 2,500 men who will be used

in columns of fifty men each. I take so large a command for the

purpose of thoroughly searching each ravine, valley and mountain peak

for insurgents and for food, expecting to destroy everything I find

outside the towns. All able-bodied men will be killed or captured...

These people need a thrashing to teach them some good common sense,

and they should have it for the good of all concerned." (Storey

and Lichauco, 120)

Dr. John Rich McDill, who served the U.S. Army in Cuba and the Philippines and later taught medicine at the University of the Philippines, made this observation, viz:

"During our military operations in the field we saw a most beautiful country, but week after week we passed through abandoned and silent towns, villages, and fields, ... The women and children, the old and feeble, and the sick, were hiding unsheltered in the woods and mountains. We, a perfectly armed and equipped army of the most powerful republic in the world, were pursuing and killing sad-eyed little brown men and boys, who were scantily clothed, poorly nourished, and almost unarmed..." (McDill, 1-2).

U.S. Lieutenant-General Nelson A. Miles, who was assigned to make an assessment of the situation in the Philippines shortly after the war,

collected reports of incidences of torture and indiscriminate killings. Here is an example:

"...Stopping at Lipa...some citizens desired to speak to me, which request was granted. ... They stated that they desired to make complaint of the harsh treatment of the people of that community; that they had been concentrated in towns through that section of the country, and had suffered great indignities; that fifteen of their people had been tortured by what is known as the water torture and that one man, a highly respected citizen, aged sixty-five, named Vincente Luna, while suffering from effects of torture and unconscious, was dragged into his house, which had been set on fire, and burned to death. They stated that these atrocities were committed by a company of scouts under command of Lieutenant Hennessy and that their people had been crowded into towns, 600 being confined in one building. Dr. Roxas stated that he was a practicing physician and that he was ready to testify before any tribunal that some of those confined died from suffocation." (Miles, 6)

An American visitor to the islands made this remark:

“I drove through Albay Province, and I found 300,000 people reconcentrated, hemp rotting in the fields, homes empty, and not a human being outside the lines - all-punished because some 300 men are in the mountains as ladrones or insurrectos. I submit that this was not justice - that it was not even a justifiable war measure. (Doherty,16)

And this comment from a Republican Congressman who visited the islands in 1902:

"You never hear of any disturbance in Northern Luzon; and the secret of its pacification is, in my opinion, the secret of the pacification of the archipelago. They never rebel in Northern Luzon because there isn't anybody there to rebel. The country was marched over and cleaned in a most resolute manner. The good Lord in heaven only knows the number of Filipinos that were put underground. Our soldiers took no prisoners, they kept no records; they simply swept the country, and wherever or whenever they could get hold of a Filipino they killed him. The women and children were spared, and may now be noticed in disproportionate numbers in that part of the islands." (Storey and Lichauco, 121-122)

And there was the so-called Balangiga massacre

on September 28, 1901, and the events that followed it. A company of 74 American troopers was attacked by disguised Filipino guerrillas aided by the villagers, counting 44 dead, 22 wounded, four missing, and only four unscathed. In the ensuing reprisal, some 250 villagers were massacred in Balangiga (Herman, 197-202).

Subsequently, U.S. General Jacob Smith swept through Samar and made it a

howling wilderness, a retaliation that drew parallel to a killing orgy as may be drawn from his orders:

"'I want no prisoners. I wish you to kill and burn: the more you kill and burn, the better you will please me,' and, further, that he wanted all persons killed who were capable of bearing arms, and did, in reply to a question by Major Waller asking for an age limit, designate the limit as ten years of age.” (Storey, 33)

General Smith's subordinate, Major Waller, made this

statement in his November 3, 1901 report:

"On the march to Liruan (a town in Samar) the second column, fifty men, under Captain Bearss, in accordance with my orders, destroyed all villages and houses, burning in all one hundred and sixty-five." (Storey, 38)

And this from an American war correspondent:

"During my stay in Samar the only prisoners that were made, so far as I know, were taken by Waller's command; and I heard this act criticised by the highest officers as a mistake which they believed he would not repeat when better acquainted with conditions in Samar... . If on their march Waller and his men shot any natives they met, their action would be fully covered by the general orders of General Smith. The truth is the struggle in Samar is one of extermination." (Storey, 38)

The new American strategy worked. By sowing fear, destroying crops and property, and causing death or inflicting pain on the non-combatants, the Americans succeeded in forcibly isolating the guerrillas from the main support base - the civilian population. The isolation of the guerrillas and the effective withdrawal of support from the civilians were the principal factors that caused the weakening of the resistance and brought the war to an end.

One author summed up the war as follows:

"...126,500 Americans saw service in the Philippine Insurrection, the peak strength of the American army at any single time was 70,000, and this army suffered battle losses of over 4,200 men killed and over 2,800 wounded. This represented a casualty rate of 5.5 percent, one of the highest of any war in American history. The financial cost of the war was over $400 million, a figure 20 times the purchase price paid to Spain. The insurgents suffered battle losses of 16,000-20,000 killed. In addition, perhaps 200,000 Filipinos died of famine, disease, and other war-related calamities. (Welch, 42)

No official estimate was ever made of the number of people killed since the beginning of the war. Numbers vary from 200,000 to 1.4 million killed; some called the war a genocide. However, U.S. General J.M. Bell made an estimate that in Luzon alone, one-sixth of the native population had been wiped out as a consequence of the war. Luzon had a population of over three and a half million, and one-sixth of that number meant 600,000 men, women, and children. (Storey and Lichauco, 121, citing Gen Bell's estimate as it appeared in New York Times of May 3, 1901, with a note:

quoted in the U.S. Senate by Mr. Hoar and never contradicted).

An American war protester made this comment:

"There is no doubt that we have caused the destruction of more lives in the last three years than the Spanish did in any century of their misrule. " (Ministers, 13).

Racist Overtones and Sympathy

During the conflict, hatred between the two adversaries amplified to higher levels, fueled mainly by racist contempt. One pretext for the war had been the assertion that the Filipinos were savages or uncivilized and, therefore, they were not entitled to consideration (Willis, 250). Aguinaldo and the Filipinos were portrayed (in political cartoons) during and after the war in general as primitive dark-skinned, thick-lipped, kinky-haired uncivilized savage children in need of America's parentage.

The Filipinos were called

niggers, gugus, khakias, and ladrones. The popular battle song among the American soldiers during the time contained a line that says:

"Damn, damn, damn the Filipinos, cross-eyed kakiack ladrones, Underneath our starry flag, civilize 'em with a Krag...". This manner of dehumanizing the Filipinos preceded violence, which Professor David Livingston Smith, in his book, Less Than Human, observed to be the usual pattern of conduct that follows the act of demeaning a fellow human being.

While strict censorship dampened unfavorable reports by news correspondents, numerous accounts of atrocities and the use of harsh methods found their way into the newspapers on the U.S. mainland, from letters of American soldiers to their families. One letter mentioned Gen. Wheaton's order to kill every native in sight in retaliation for the fatal shooting of an American soldier whose stomach was cut open; about 1,000 men, women, and children were reported killed that night; the letter ended with these words: "

I am in my glory when I can sight my gun on some dark skin and pull the trigger." (Atkinson, 66; Storey, 25 and Swift, 253)

Some of these letters led to investigations by the U.S. Congress. A transcript of one such investigation contained the testimony of two American soldiers, Charles Riley and William Lewis Smith, describing in detail the administration of water torture to the

presidente of Igbarras, Iloilo, and three of the town's policemen, including the subsequent burning of the whole town (Riley, 2-4). Unfortunately, the investigations did not result in legislative acts that could have mitigated the repressive policy of President McKinley in the Philippines. The hearings were more a preponderance of justification for the acts of the American soldiers in the field than the condemnation of their actions.

Similarly, the Court Martial of some officers and men handed down a judgment that may be likened to a slap on the wrist. In particular, the punishment meted out to General Jacob Smith, the author of the destruction of lives and property in Samar, was a mere reprimand.

Some high officials in the McKinley administration and in the military had publicly expressed their support of extreme measures in regard to American policy in the islands, viz:

"It may be necessary to kill half the Filipinos in order that the remaining half of the population may be advance to a higher plain of life than their present semi-barbarous state affords." , or, "... the extermination of the natives is America's only hope of being able to establish a stable government." (Van Meter, 368)

An Associated Press report datelined New York, July 28, 1900, carried this statement, viz:

"A dispatch to the Herald from Paris says: 'Jean Hess, French explorer and writer on colonial subjects, after passing three weeks at Manila, wrote a long letter, dated Hongkong, June 20. Mr. Hess says the idea of independence is in the heart of the Filipino race, and will only be destroyed by destroying the race." (Van Meter, 367)

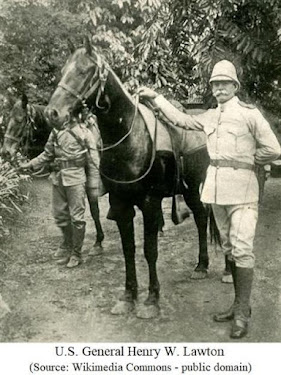

On the other side of the spectrum, a fitting tribute to the Filipino soldier for his bravery, fortitude, and sacrifices was given by no less than General Henry W. Lawton, the American officer who was killed in the battle against Filipino forces at San Mateo, Rizal, viz:

"Taking into account the disadvantages they have to fight against in arms, equipment and military discipline, - without artillery, short of ammunition, powder inferior, shells reloaded until they are defective, inferior in every particular of equipment and supplies, - they are the bravest men I have ever seen.... What we want is to stop this accursed war.... These men are indomitable. At Bacoor bridge they waited until the Americans had brought their cannon to within thirty-five yards of their trenches. Such men have the right to be heard. All they want is a little justice." (Story and Lichauco, 110-111)

And there were also some American soldiers who joined the Filipino cause. The likes of Arthur Howard, Henry Richter, Gorth Shores, Fred Hunter, William Denten, Enrique Warren, and the legendary black American David Fagen, to name some, saw injustice in their cause and decided to fight the flag they had sworn to defend (Tan, 250).

The Anti-Imperialist League in the United States and some members of the U.S. Congress also sympathized with the Filipino cause. They were very critical of the policy of the administration of President McKinley. Similarly, the Democratic Party publicly expressed its support for Philippine independence by making it one of the party's programs in its platform. Aguinaldo pinned his hopes on the victory of William Jennings Bryan, the party's presidential candidate in the 1900 elections, but unfortunately, he lost to McKinley.

Re-educating the FilipinosThe

first American-controlled schools established for the education of Filipino

children were initiated by the United States Army right after the defeat of the

Filipino Republican Army. One observer

wrote:

“Possibly never before had a great army been given so

diverse a task as the one devolving upon the American army in the

Philippines. While pacifying the

provinces as expeditiously as the jungles and season permitted, they

established a complete civil government and conducted courts, custom-houses,

post offices, and schools for the Filipino Children. Great godowns in the commissary department in

Manila were filled with all kinds of school supplies, including books, charts,

pads, pencils, etc. Commanding generals

were also departmental superintendents of education; examinations were held,

and soldiers qualifying were detailed to teach schools. In the fall of 1900, when Mr. Taft and

companions of the second civil commission arrived in Manila to take over the

administration of the Philippines, they found a school system that needed

little radical changing to meet their own plans for the education of the

Filipino children” (Briggs, 76-77)

It

challenges the mind of any independent observer as to why the rush to implement

a new, unprepared education system for Filipino children by untrained teachers,

given that the existing old system could have served as a transition. Was it because the Americans were hell-bent

on isolating the Filipinos from their

recent past by immediately initiating the Americanization of a subdued,

unwilling people and erasing from their memory the criminal aggression waged by

the McKinley administration?

Against the backdrop of the great American heritage, this McKinley intervention in the Philippines was destined to become an ugly episode in the glorious pages of American history. It would be a contradiction to the long-held constitutional and democratic principles of liberty that the American people hold dear - that men are created equal and have inherent rights to freedom and democracy. Certainly, American authorities would not allow the true story of the Philippine conquest to blemish American honor. Therefore, it would be logical to conclude that steps were taken to muddle this segment of Filipino history, erase it from the memory of the Filipinos, make them forget the horrors they went through, and hide it from the prying eyes of the future generation.

True enough, steps were taken to make Filipinos forget!

Francis Burton Harrison, the first Democrat-appointed Governor-General of the Philippine Islands, whose administration was marked by liberality and sympathy to the Filipino cause for independence, described the steps taken:

"The exhibition of the Filipino flag, under which they had fought their war against us, was made by statute a criminal offense. Patriotism was never encouraged in the schools, nor ideas which tended to arouse their own national consciousness. Everything which might help to make the pupils understand their own race or think about the future of the country was carefully censored and eliminated. Nevertheless, the good sound stock of American ideas which they received instructed them inevitably in our own democratic ideals, and in our pride in own liberties." (Harrison, 45-46).

The United States established and ran a colonial government employing only an American Governor-General and a few of their nationals. The towns and cities in the provinces and the civil service were manned by Filipinos, many of whom were ranking officers of the defunct Filipino Republican Army. The Supreme Court justice was even a Filipino. Thus, the proven capability of the Filipinos to administer government machinery exposed the hypocrisy of the McKinley administration in alleging that Filipinos were savages and unfit for self-rule and validated the claim that President McKinley deceived the American people into believing that America was not engaged in imperialist expansionism but rather in a humanitarian mission to uplift Filipinos that he called a savage people.

The Sedition Act of 1901, coupled

with the Criminal-Libel Act, practically silenced any overt opposition to the

American administration, patriotic expression, or gathering by Filipinos under

threat of criminal prosecution. Those

who participated in the war of resistance and refused to take the oath of

allegiance to the United States were exiled to the Marianas. The result was an atmosphere of complete

cleansing or purging of the ideals and aspirations for freedom and self-government. It was not surprising that published accounts

about the revolution and the resistance to the American invasion, such as the

one of Ricarte and Alvarez, only came many years later.

The irreconcilable former General of the Filipino Republican Army, Artemio

Vibora Ricarte, who took to his grave his refusal to take the oath of allegiance to the United States, preferring solitary confinement, then a self-exile in Yokohama, Japan, saw beyond the façade of American altruism an insidious design when he said:

"The

truth is America taught our young people the things that commemorate

the lives of Lincoln and Washington in order that we will forget in

our hearts the exemplary deeds of our nation's great heroes. The

Americans believe that once we are able to speak good English is

proof enough that we have learned, yet in our minds is being

instilled a wrong thinking, the superiority of the white race."

(author's translation of Tagalog text found in Ricarte [Kabataan], 12).

War relics and voluminous captured Filipino government records and documents officially labeled Philippine Insurgents Records (PIR), estimated to weigh three tons, were shipped to the United States and became inaccessible to local historians and researchers. Captain John R. M. Taylor, who, for a time, was designated caretaker of the records, did extensive work of cataloging, translating, and preparing the galleys for the publication of a book. The first attempt at publication in 1906 did not materialize because the expected corrections from Governor-General William Howard Taft did not come. The second attempt in 1909 was also shelved because the review James LeRoy was supposed to do was not completed. In any case, the printing of the book was finally suppressed because Taft, who later became president of the United States, did not consider it politically expedient to publish the book. (Farrell, 404)

These records were returned to the Philippine government by virtue of a U.S. Legislative Act of July 3, 1957, and are now in the custody of the National Library. The documents have become fragile due to the passage of time, but some microfilms can be used on most of them in lieu of direct physical handling.

However, in 1971, the book was eventually published in the Philippines after 70 long years, with very limited distribution, by the Eugenio Lopez Foundation, under the supervision of an editorial panel headed by Renato Constantino. Here is an excerpt from Constantino's introduction:

"...At a time when we were proving to the world the reality of our nationhood and our capacity for self-rule by ousting a colonial master and resisting the aggression of another, we lost another part of our history. Our records were captured from us. Tons of "insurgent" records were shipped to Washington, there to remain unread for over half a century except by those to whom permission was granted by the U.S. Adjutant General of the Army. Thus this phase of our history is still relatively unexplored. We have fragments of knowledge about this period from the writings of those who have seriously endeavored to elicit the truth from the inadequate materials at hand, but on the whole, we are still relatively ignorant of what really happened. This ignorance has been compounded by our acceptance of a version of our history consonant with colonial policy.." (Taylor[I], x)

American teachers called the Thomasites (after the steamship that brought them to the islands) came to inaugurate an American-sponsored public school system. English supplanted Spanish (a language change that was not done by the Americans in Puerto Rico or Cuba) and with it went the loss of Hispanic literary and intellectual heritage, making the succeeding generation of Filipinos fertile grounds for the propagation of the good sound stock of American ideas. (Harrison, 46)

Filipino schoolchildren were taught to revere America and belittle the land of their birth. The first line of a beautiful Tagalog love song, Lulay, "Ako'y ipinanganak sa tuktok ng bundok," was translated into English as "I was poorly born on the top of the mountain," emphasizing the state of being poor. The song actually tells the story of a lover - some kind of a demigod - who was born on top of a mountain with the clouds as his cradle while he played with thunder and lightning caressing his hair. In a similar case, the first line of the popular Tagalog folk song, the Bahay Kubo, was translated into English as "My nipa hut is very small," again, the emphasis on smallness. The translation negated the message extolling a small farm where plenty of vegetables are raised.

From these kinds of schemes arose the glorification, if not idol worship, of practically anything American by the indoctrinated Filipinos who did so consciously, even at the expense of their own dignity. For many decades, the terms "Made in U.S.A." and "stateside" determined the buying pattern of Filipinos. Noteworthy were the illustrations of Filipinos showing images with pointed noses and a preference for Caucasian looks as the model of the beautiful and handsome and in recruiting movie stars.

Another critical step the American authorities took was to discredit Aguinaldo and brand him a villain as Aguinaldo himself expressed at one time. He said:

"I have been loyal to America and the Americans. I have at all times acted upon their advice, complied with their desires, yet in their daily journals they endevour to humiliate me before my people. They call me thief, renegade, traitor, for no reason. I have done them no harm; I have assisted them to their ends, and they now consider me their enemy. Why am I called a renegade, traitor, thief?" (Sheridan, 90)

This strategy was reinforced by making Rizal overshadow the contributions of Aguinaldo, viz:

"Among

other things the Filipino people lacked to make them a nation was a

hero - a safe hero, the only safe ones, of course, being dead.

Aguinaldo held the highest place in the eyes of his countrymen, as

the leader of the recent insurrection, but he was ... one who might

be of considerable danger to the American administration. It was

expedient to establish a hero whose fame would overshadow that of

Aguinaldo, and thereby lessen that leader’s ability to make future

trouble. ... Governor Taft, ... at once fixed on Jose Rizal…"

(Crow, 53-54).

Governor Taft's designation of Dr. Jose Rizal as the national hero was calculated not only to overshadow Aguinaldo's stature and minimize his ability to make future trouble. It also had the effect of stigmatizing the Spaniards as villains, not only for the oppressive centuries of misrule but, more particularly, for executing the hero Rizal, at the same time, bestowing the honors on the Americans as the savior of the Filipinos for making possible the complete overthrow of the Spanish authority in the islands.

If Aguinaldo were to remain respectable in the eyes of his compatriots, the commemoration of his accomplishments would highlight not only his victory over the Spaniards and the republican government he established but also the unjust war of conquest waged by President McKinley on the Filipinos that Aguinaldo heroically resisted. In declaring Aguinaldo a traitor, which gained headway during the American period and is now proliferating in social media, the villains in the Filipino national consciousness would solely be the Spaniards who ruled for three centuries and killed the national hero Rizal. This diversion of focus led the Filipinos into a trap, and their national consciousness was rendered in terrible confusion. All the great achievements of their ancestors - the national flag, the national anthem, the June 12 Independence Day, the first republic in Asia, that was attained through the leadership of Aguinaldo would be taken for granted and looked upon with doubt and disbelief. The image of the Americans who subjugated the Filipinos after atrocious warfare was waged against them would be secured and idolized, and the Americans would be absolved from being remembered as the butcher of the Filipinos, the pillager of their land, and the destroyer of their republic.

While the higher legislature, judiciary, and executive positions were Filipinized during the later part of the American colonial government, the position of head of the Education Department was kept by an American (Philippines[Bureau of Education], 25). As late as 1951, a Grade IV pupil was still being taught to sing Star-Spangled Banner, God Bless America, America the Beautiful, American children's music, American folk songs, etc.

As soon as the same child stepped into High School, this student would be required to study American history in the First Year and memorize the address of Lincoln at Gettysburg or the poem, The Song of Hiawatha, in succeeding years. So, for almost five decades, starting from the American colonial regime, through the Commonwealth and World War II, and further on towards the period of the independent Filipino government, the process of re-educating the Filipinos was at work.

And to wrap it all up, the Filipino freedom fighters were called "insurrectos" (and then bandits and ladrones), and the Philippine-American war, the "Philippine Insurrection." The war was tucked under the generic caption "Spanish-American War" in books and publications circulated in the United States. Yet, the Americans fought the Spaniards in the Philippines in the so-called Spanish-American War for only three days, yes, three days - one day for the battle of Manila Bay, another day for the raid on San Antonio Abad blockhouse in Ermita, and another day for the surrender of the city of Manila. The truth is all the fighting in the Philippines against the Spaniards during the Spanish-American war was done by the Philippine Revolutionary Army of General Emilio Aguinaldo. In comparison, the duration of the Philippine-American war was for a period of three years plus another three years to clear out the remnants of the resistance movement. And yet considering the magnitude and significance of this war that McKinley fondly called "splendid little war," it was not given the full distinction and coverage it deserved. After so many decades, it was only later that the label "Philippine Insurrection" was replaced by the phrase "Philippine-American War" in subsequent references.

In essence, the American conquest of the Philippines was not just a case of subjugating an unwilling people. It was also a case of making the same people forget that they were subjugated.

Quo Vadis Filipino?

The new Filipinos that emerged out of the decades of re-education were Filipinos in appearance but Americans in thought, word, and deed. True to Harrison's specifications, this new Filipino spoke English fluently and knew much about American ideals, history, arts, literature, and music by heart, but had a vague notion of their ancestors' struggle for freedom or their sacred dreams and aspirations that drove them to arms. He would usually turn into a very competent professional but would lack one very important trait – patriotism, thanks to the methodical classroom strategy that Harrison described.

He may not realize it, but the Filipino today is a replica of his predecessor, the re-educated Filipino. He still lacks a clear understanding of history and is pulled down by the heavy burden of a corrupted sense of identity. In the preface of his book, "Saga and Triumph", Onofre D. Corpuz summed it up as follows:

"The decade of 1896-1906 marked out the watershed of Filipino nationalism. It is therefore incredible that, after a full one hundred years, the centennial of the revolution against Spain in 1996, and that of the Filipino Republic in January 1999, passed without a full-length history of that truly epic struggle and the Filipinos' unprecedented achievement. It is histories that weave the diverse strands of a people's past into the fabric of their collective memory. It is the quality of that fabric of memory that basically defines the quality of their life over time. And it is the remembering of that shared memory that enables a people to image themselves as a nation, to sense their destiny in the future, and to realize that destiny through the will to cope with the challenges of the present. Without good histories, the collective memory is fragile and fragmentary." (Corpuz, xii)

In an article entitled The Philippine Revolution in our Collective Memory, Corpuz lamented the deplorable state of some historical works, saying: "... Some works totally miss the point of the revolution: they depict its greatest leaders in deep personal conflict with each other. Thus, when put together, these works leave us in ignorance of the revolution in its true light: the epic struggle that today remains the watershed of Filipino nationalism."

Alfredo Saulo is more forceful in expounding about this malady when he says:

"For mistakes of omission, plain ignorance, or evasion of unpleasant historical facts, our historians have fostered a kind of historical writing that is incompatible with our status as a free and sovereign nation. It was under this colonial historiography that three generations of Filipinos have been brought up - miseducated - their sense of values westernized to the extent of forgetting their national interest. One would notice an almost total absence of nationhood among the younger generation, compounded by a lack of appreciation of the heroic sacrifices of their freedom-loving forebears. Aguinaldo, who liberated Las Islas Filipinas (the Philippine Islands) from more than three centuries of Spanish subjection, is derided and maligned to this day by unenlightened Filipinos." (Saulo[Aguinaldo], xxxv-xxxvi)

Patriotism binds a country together. It inspires the people to make sacrifices for the well-being of the nation. A country can only succeed if its people make sacrifices. But without patriotism, how could there be a sacrifice?

The success of the government's program to uplift and create a prosperous society that relies on OFW remittances, earnings from BPO, foreign aid, foreign investment, preferential treatment, free trade, or other economic schemes is doubtful without first rejuvenating the Filipino mind, i.e., rekindling it with the spirit of 1898 – the love of country and the aspiration to be free and independent.

To proceed in this direction, the Filipino must reclaim the patriotism of his ancestors who sacrificed life and property for the country and whose exemplary deeds are held hostage by the muddled past. It would require memorializing these legacies in the classrooms for the reawakening of the coming generation. Instead of pitting one hero against another in a cockfight-like fashion, Filipino historians should focus on rewriting the defective history now taught in the classrooms. Introducing the reoriented history in the textbooks will unlearn the misconceptions carried over from the past and the true accounts of the great sacrifices and contributions of the heroes will leave a patriotic imprint in the minds of the young people.

The prolific historian Dr. Gregorio F. Zaide propounded five specific reasons (Saulo, xli) why the rewriting of Philippine history is an urgent necessity; namely:

1. As a free and sovereign nation, we should write a new history of our country - a history of Filipinos, for Filipinos, and by Filipinos;

2. Every generation writes its own history. Our generation must, therefore, have a history that shall reflect its restless spirit, its ardent desire for reforms in government and society, and its passionate yearning for a better life;

3. The errors or inaccuracies that have long been enshrined in our published history books must be corrected;

4. There still exist many gaps in our recorded history caused either by a lack of source materials or by inadequate knowledge of historians. These gaps must be filled up to broaden our historical knowledge; and

5. It is high time that we interpret our historical facts from the Filipino point of view.

Final word In the same manner that the classrooms were utilized to erase the Filipinos' unprecedented achievement from their collective memory, they should be used to reclaim their lost and forgotten histories. In so doing, the younger generation of Filipinos is instilled with pride in their great heritage, which will germinate the seed of patriotism and hasten the reformation of the national psyche. This should lead to recognizing and acknowledging the capacity of Filipinos to do great things, just as Rizal, Bonifacio, or Aguinaldo had done. It will eventually give the Filipino today the courage and strength to remedy the present and the confidence to approach the future.