(This write-up is identical to the article with the same title found on pages 142-165 of the book entitled "The Filipino Tragedy and Other Historical Facts Every Filipino Should Know," published by the author. The sources and references indicated here are contained on pages 402-415 of the book.)

Aguinaldo is the liberator

of the Filipino people. He is the

founder of the first Filipino state known as the First Philippine Republic (or

the Malolos Republic) that promulgated a constitution bestowing Filipino

citizenship to all residents of the archipelago, not anymore as “Peninsulares,”

“Insulares,” “Indios,” and “Naturales.” He also initiated the campaign to

recognize this first Filipino republic by independent nations of the world.

This fact is unclear or misunderstood by Filipinos because of miseducation and

outright lies and propaganda proffered by interest groups.

According to U.S. General Douglas MacArthur, he

was the very incarnation of the Filipino desire for liberty and freedom, while

President Lyndon B. Johnson said his monument is the Republic of the

Philippines

The Rise and Fall of

Cavite

Aguinaldo provided the first Filipino victory of the revolution at the battle of Imus [district of Alapan - Author] (Ronquillo, 287-297). Had the Cavitenos been defeated by General Aguirre, it is almost certain that the nascent rebellion would have been quickly crushed. Instead, by inflicting a crushing defeat upon Aguirre and the Spanish forces, Aguinaldo catapulted revolutionary morale to new heights.

Governor-General Blanco had to wait till he had sufficient troops before daring to attack Cavite again. He returned to Cavite in November 1896, but Aguinaldo handed him a humiliating defeat at Binakayan (Ronquillo, 345-358). Aguinaldo’s victory gave the Cavitenos and other revolutionaries time to consolidate their victories and secure their territories from isolated Spanish garrisons, all of which raised Aguinaldo's fame and prestige and secured him a place of leadership among the revolutionary commanders.

With these victories, he liberated the province of Cavite, which became the refuge for besieged Katipuneros from nearby provinces. And in an expression of gratitude and recognition of his leadership, he was elected president of the revolutionary government at Tejeros. However, internal disputes and the stubbornness of Bonifacio in refusing to merge forces under a unified command and, at times, his reluctance to provide aid to Aguinaldo in the face of the massive Spanish offensive (Saulo[Aguinaldo], 140-141) contributed to the untimely fall of Cavite.

Aguinaldo saved the revolution and turned defeat into a stalemate by forcing the Spaniards to sue for peace at Biak-na-Bato. The agreement provided respite for the battle-weary revolutionaries. It shielded them from bodily harm and reprisal while obtaining a promise of long-sought reforms and a considerable sum of money in exchange for the surrender of the arms and exile of the leaders abroad.

Decisive Victory Over the Spaniards

The second phase of the revolution commenced upon the return of Aguinaldo in May 1898 from Hong Kong, and he immediately took to the task of organizing an army and supplying it with weapons purchased abroad out of the funds secured from the peace pact of Biak-na-Bato. Through foresight and audacity, he raised the level of revolutionary thrust by building a modern army with better weapons and, in the process, defeated the Spanish army, leading to the establishment of the first Filipino state, represented by the First Philippine Republic that administered Luzon and various islands in the Visayas and some parts of Mindanao, excepting the city of Manila and isolated garrisons. In less than two months, Aguinaldo and his forces conquered practically the whole of Luzon. He surrounded the city of Manila with his troops, sent Gov. Gen. Basilio Agustin a demand to surrender, and laid a siege awaiting Agustin’s reply. He set his sights on the Visayan islands and Mindanao, sending expeditionary forces to help local revolutionaries take control of their territory.

Here’s an eyewitness account of

Aguinaldo’s first major victory against the Spaniards in Cavite:

As the prospects for fighting between the United States naval forces and the Spanish troops on shore were now practically nil, I devoted my time to watching the proceedings of the Filipinos under Aguinaldo. Within a week after his arrival in Cavite he had about 1,000 men under arms. Admiral Dewey gave him a large number of Mauser rifles and a considerable quantity of ammunition, captured from the Spaniards, and in a day or two a small steamer called the Faon, an assumed name, by the way, came into port from Canton, bringing about 3,00“0 stand of Remington breechloading rifles and a large stock of cartridges for these pieces.

“On the night of May 26th Aguinaldo sent 600 men across Bakor Bay to land between the detachment of Spaniards who were holding Cavite Viejo (Old Cavite) and the detachment quartered in the powder magazine, a little to the east of Cavite Viejo. The garrison in each of these strong positions was about 300 men, so that the insurgents were represented by a force equal to that of their enemy. But, while the Spaniards had fully 1,000 men and several pieces of artillery within easy call of both these positions, the natives had no artillery and no possibility of getting reinforcements. Once landed on the Old Cavite side of Bakor Bay, they must fight it out for themselves.

“On the morning of May 28th a detachment of Spaniards attacked the insurgents and were not only repulsed but forced to surrender, the insurgents capturing in two skirmishes 418 Spaniards, including fifteen officers. The country where these affairs took place was covered with a thick tropical undergrowth, while numerous streams and swamps permitted no military order to be maintained.

“… On May 29th, before the sun had yet risen, General Aguinaldo reinforced his troops on the mainland with about one thousand men. I expected to witness a charge over the narrow neck of land that connects Cavite peninsula with the mainland, where the Spaniards were known to have at least one field gun and the bulk of their troops. Before noon, however, General Aguinaldo told me he had changed his plan, because the Spaniards held the peninsula with such a large force that he feared an assault would not be successful. If he failed he would not be able to reinforce his men on the other side of the bay without taking great chances from the Mausers of the Spaniards stationed at the Bakor magazine and at Old Cavite. Also, in case the Spaniards should bring heavy reinforcements from Manila, his men would be caught between two fires, where they might all be captured or killed. As this was the situation he refused to give me any assistance to get to the front, and would not even give me a guide to show me where to land my boat on the other side.

“… As I was intently watching the events on shore I did not notice what was happening behind me and was suddenly surprised to hear the roar of a heavy gun. I could tell by the scream of the projectile as it passed over me that it came from a rifled gun of large calibre, and for a moment I thought the Petrel must have entered into the fight. I could not discover where the shot struck; but looking back to Cavite, I distinguished a group of rebels surrounding four muzzle-loading rifles that pointed toward the Spaniards from the Cavite wall. In front of the guns a long stovepipe was throwing out a column of signal smoke like the one on the beach near me. This was the plan Aguinaldo had been keeping in reserve, and he was now letting his men at the front know he was ready to take part in the fight.

“… Like ants now, the little brown men swarmed along the beach toward Bakor Church. This was the only place where the Spaniards seemed to be strong except at Old Cavite. It was evident that the rebels were pressing upon them harder from the land side than from the beach; for, while the field piece fired a few shots and reports of rifles were frequent, fewer bullets came in my direction.

“… In a few moments two or three wounded men staggered to their feet, waved their hats in the air, and then sank down, exhausted but victorious. Presently the rebel flag-a band of red above and blue below, with half a white diamond near the flagstaff-fluttered from the roof of Bakor Church. Everything on the beach had been captured except Old Cavite.” (Stickney, 75-81)

Felipe Buencamino, a Colonel in the Spanish army in command of a regiment of militias, observed the movements of the rebel army while he was in detention in Aguinaldo’s camp after a failed mission on orders of Spanish Governor-General Basilio Agustin to convince Aguinaldo to fight alongside Spain against the Americans. And he had this to say in his letter to Agustin, urging the Governor-General to surrender:

"… Having been sent back to my prison, …I could see … the passing of wagons laden with arms, cannon, and ammunition, which would go to the landing and unloaded on cascos, small and large craft which came every day to this city with large masses of men whom I estimate would amount to more than four thousand. Vessels loaded with arms, ammunition and former insurgents would also come from Hongkong and afterward, I learned from those who visited me, after I was released from solitary confinement, that on the 28th of last month a column of three-hundred men of the Marine Infantry, commanded by Major Pazos, was captured between Imus and Kavite Viejo, and at the same time firing was heard on all sides of this province, which showed the general movement of the new revolution.

“I also learned that General Pena with his staff surrendered without exchanging a shot; surrendering cannon and other arms, public and Government treasure, with 200 volunteers from Apalit recruited by me, but which General Monet delivered to the Army Captain, Don Jesus Roldan. The news also came to me that the detachment of Bacoor composed of 200 volunteers from my regiment and over one-hundred men of the Marine Infantry, in command of Lieutenant Colonel, Don Luciano Toledo, having been besieged, … had to surrender; as did also the detachment of Baccor on the following day.

“And thus, in less than six successive days, the detachments of Imus, Binakayan, Noveleta, Santa Cruz de Malabon, Rosario, Salinas, Kavite Viejo and other pueblos of this province which is now in the power of Don Emilio Aguinaldo surrendered.

“But that is not all because there also came as prisoners from Kalamba, Binan, Muntinlupa and from the province of Bataan - among them the Governor and Administrator with their wives and daughters - 200 volunteers of the Blanco Regiment with its captain, Gomez, and 4 officers, besides 170 Cazadores with Lieutenant Colonel Baquero. Colonel Francia escaped to Pampanga, leaving the volunteers.

“In a word: in eight days of operations, Don Emilio Aguinaldo has, here and in the conquered pueblos, 2,500 prisoners and more than five thousand arms, 8 cannon and a large number of friars, which has decided him to direct an attack on Manila, in combination with his forces from Bulacan, from this province, and those from that capital, which will amount to some thirty-thousand men armed with rifles and cannon; sending his forces from Bataan and Nueva Ecija to surround General Monet’s, who is in Pampanga, and those of Paciano Rizal in Kalamba to invade Batangas." (Taylor, v3:92-97)

Buencamino's account of Aguinaldo’s victory over the Spanish army is confirmed by U.S. General Thomas Anderson in this interview published in the North American Review of February 1900, viz:

"At that time [July 1898] the insurgent Filipinos had driven the Spanish soldiers within the defenses of Manila and had them completely invested on the land side by light field works, which they held with about fourteen thousand men. They were poorly armed and equipped, yet, as they had defeated the Spaniards in a number of fights in the field, and had taken four thousand prisoners, it may be asserted in the vernacular of the camp that they ' had the morale on them.' The Manila garrison was so demoralized at that time and so incomplete was their line of defense that I believe it would have been possible, by coming to an understanding with Aguinaldo, to have carried their advance works by storm and to have captured all of the city, except the walled city or the old Spanish town. Under existing orders we could not have struck a bargain with the Filipinos, as our Government did not recognize the authority of Aguinaldo as constituting a de facto government; and, if Manila had been taken with his co-operation, it would have been his capture as much as ours. We could not have held so large a city with so small a force, and, it would, therefore, have been practically under Filipino control. (Philippine Information Society, 7-8)

Liberation of Luzon and some parts of Visayas and Mindanao

The Filipino government extended its successful

destruction of the Spanish Army not only in the province of Cavite but also in

the whole island of Luzon and in the Visayas and Mindanao. Leandro H. Fernandez describes this campaign of

Aguinaldo in his book, “The Philippines Republic,” viz:

“This first

expedition, under the command of a young officer, Manuel Tinio, was detailed to

operate in the Ilocos region, in north-western Luzon. It started its march to

the north from San Fernando de la Union, then already under insurgent control. The expedition met no serious

opposition, for the Spanish forces retreated at its approach; and Tinio,

between August 7 and 17, occupied the important towns of Bangar, Tagudin, Vigan

and Laoag. At Bangui, a coast town in

Ilocos Norte, the Spanish detachments, numbering in all from two to three

hundred men, finding themselves cut off, surrendered. By the end of August the

control of the Ilocos provinces, including Abra, had passed to the Filipino

Government.

“The next important

expedition was that sent to the Cagayan valley, in north-eastern Luzon, under

the command of Colonel Daniel Tirona. It was made up of six companies conveyed

by the insurgent transport ‘Filipinas’ to Aparri, at which port it arrived on August

25. Operations against this town were

begun immediately: a company was posted at the village of Linao, another at

Kalamaniugan, and a third at the town of Lal-lo, formerly the seat of a

diocese, so that Aparri was completely isolated. The Spanish detachment, seeing

that the people, hitherto considered ‘loyal to Spain, would not fight against

their fellow Filipinos’ and believing further resistance useless, capitulated.

With Aparri in their hands, the expeditionary troops occupied the important

coast towns; then, on August 3, they also took Tuguegarao. The main towns in the province of Isabela were likewise

taken possession of, including Ilagan, the provincial capital. On the same day

(September 14) that Ilagan was occupied, Bayombong, the capital of the province

of Nueva Vizcaya, capitulated to another force of revolutionists under Major

Delfin Esquivel. Thus the entire Cagayan

valley, as well as the Batanes islands, off the north coast of Luzon, which

were also occupied at this time, passed into insurgent hands.

“The extension of the

authority of the Filipino Government to the Bicol region, in south-eastern

Luzon, came about in a different manner. In Ambos Camarines and Albay

conditions had never been satisfactory since 1896, and the people in the chief

towns of Daet, Nueva Caceres and Albay were ready to join the revolt. In Daet

and Nueva Caceres feeling ran high, so much so that the Spanish officials and

residents of the former abandoned it in August, while those of the latter were

besieged and disarmed in September by local revolutionists. A provisional government was formed, and ‘the

Philippine Republic began to rule’ the province. Albay and Sorsogon followed

the example of Ambos Camarines and set up their own local governments. That

established in Albay, on September 22, which was patterned after the scheme

decreed on June 18, immediately notified Aguinaldo of its constitution,

declaring its ‘most sincere adhesion to the Republican Government of the

Philippines’ and announced its readiness to turn the control of affairs over to

the representative of the Central Government on his arrival. When

Vicente Lukban, therefore, arrived in October at the head of an expedition, his

mission was accomplished without any difficulty, and, in a few weeks, the Bicol

provinces were thoroughly committed to the revolution.

“The islands adjacent

to southern Luzon came under insurgent control at different times. Northern

Mindoro was early the objective of a small expedition from Batangas, and, on

July 2, the town of Calapan, after a siege of thirty-one days, was occupied by

the revolutionists. Marinduque, lying close to the Tayabas coast but belonging

to Mindoro, organized itself about this time, and, in pursuance to a petition

by its inhabitants, it was authorized by the Revolutionary Government on July

20 to constitute itself an independent province. From Marinduque and the Tayabas coast, small

expeditions were sent to the island of Masbate, which, on November 9, became,

with the near-by island of Ticao, a ‘politico-military district’ of the

insurgent government.' The Romblon group, i.e. Romblon, Tablas and Sibuyan

islands, early in September, ‘ was already in the hands of the Bisayans who

inhabit this group, aided, however, by a few Tagalog soldiers from the mainland

of Luzon.’

“As in Luzon and the

adjacent islands, the authority of the Filipino Government was extended readily

to the Bisayas proper. Here however, with the exception of Panay and Negros,

little or no fighting occurred between Filipinos and Spaniards. General Diego

de los Rios, who had been appointed by the Spanish Government ‘governor and

captain-general’ of Bisayas and Mindanao, found in October, 1898, that all was

not well with the territory of his command, where he discovered secret plots

even among the native soldiers he considered loyal, and he, therefore, decided

to order the concentration of his troops in Iloilo and in Cebu. Later, in December, after the signing of the

treaty of peace at Paris, he withdrew from these points, and retired to the

distant outpost of Zamboanga, where he managed, for some months, to maintain a

semblance of Spanish rule. His withdrawal from these places was the occasion

for the open assumption of control by local revolutionary authorities, which

then generally existed in one form or another.

“Leyte and the

near-by island of Samar which had been reached by emissaries from Masbate and

southern Luzon as early as August, was ripe for trouble even before the virtual

evacuation by the Spanish in October. Thereafter troops were sent from Luzon,

and General Vicente, Lukban was ordered to take charge of affairs. On January 1, 1899, he issued a long

proclamation addressed to the ‘Citizens of Samar and Leyte’ calling on them to

stand united and to live in peace under the protection of the new-born Republic.

But even before this time, the people of Tacloban, capital of Leyte, had

constituted a provisional government and raised the Filipino, flag, declaring

their solemn adherence to the Philippine Republic and their loyalty to

Aguinaldo and pledging their cooperation for the furtherance of the ideals of

the new regime. What had occurred in

Leyte, also took place, in a general way, in Samar, Cebu and Bohol . However,

while the revolutionary party in Cebu, where a local government had been

established on December 25, was quite strong, that in Bohol was comparatively

weak at this time a circumstance due, perhaps, to the fact that only a few

rifles had found their way thither and no armed expedition had reached the

island.

“In Panay island the

revolutionary movement began as early as July or August, when a ‘regional

committee’ was established at Molo, a

suburb of Iloilo. The Panay revolutionists not only conducted a propaganda to

stir the people to action, but also sent, in September, agents to Luzon to

purchase arms and to ask the aid of the Central Government at Malolos, and, on November 17, organized a ‘provisional

revolutionary government’ at Santa Barbara.

As a matter of policy and in response to the request made, expeditionary

troops were sent from Luzon: first from Cavite to Antique late in September under Leandro Fullon, then from Batangas

to Capiz about the middle of November under Ananias Diokno, commander-in-chief

of the expeditionary forces to Panay. The following month, when General Miller

was ordered by General Otis to proceed to Iloilo harbor, more reenforements

were hurried by the Central Government to Panay.' Meanwhile, the ‘provisional

revolutionary government’, later reorganized as the ‘council of the federal

state of Bisayas’, had put in the field its troops under the supreme command of

Martin Delgado. About the end of November, these commands - Fullon's in

Antique, Diokno's in Capiz, Poblador's (a subordinate officer of Delgado) in

the district of Concepcion, and

Delgado's; in Iloilo - had virtually freed Panay island from Spanish control.

In the beginning of December, all that was left in the island to Spain was the

town of Iloilo, which, on December 24, was abandoned finally (the Spaniards

sailing to Zamboanga) in the hands of its mayor, Vicente Gay, who promptly

turned it over to the revolutionists the following day. The last week of

December, 1898, therefore, saw the Filipinos undisputed masters of the three

provinces.

“The loyalty of the

Panay revolutionists to the Filipino Government is sometimes doubted; but there

are documents to show that the men who composed the ‘council of the federal

state of Bisayas’ not only recognized the authority of the Central Government,

which, according to them, was ‘that of the whole Philippines’", but also

acclaimed Aguinaldo and the Filipino flag. There was an unmistakable desire on

their part for a federal union, to be composed of the three regions of Luzon,

Bisayas and Mindanao, instead of a centralized state, which the functionaries

in Luzon favored and finally embodied in the Malolos constitution; but beyond

this desire they did not go. That they were sincere in their adherence to the

Filipino Government was shown best in their repeated refusals to allow General

Miller to land troops at Iloilo without previous authorization from Malolos,

inasmuch as this, they said, ‘involved the integrity of the entire republic.’ In the words of Roque Lopez, president of the

"council of the federal state, ‘the supposed authority of the United

States began with the treaty of Paris, on December 10, 1898,’ but " the

authority of the Central Government of Malolos is founded in the sacred and

natural bonds of blood, language, uses, customs, ideas, sacrifices, etc."

Further on he adds: ‘we insist in not giving our consent to the disembarkation

of your (Millers) troops without an express order from our Central Government

at Malolos.’

“The people of Negros

island, which lies south-east of Panay, were drawn into the insurgent ranks

mainly through the infiltration of revolutionary ideas from Iloilo. Although a

revolutionary committee had been established early at the town of Silay, the actual

uprising did not begin until after the receipt, on November 3, of a letter from

Roque Lopez, giving news of the successful course of the war in Iloilo. Encouraged by the example of this province,

the revolt began on November 5 under the leadership of Aniceto Lacson and Juan

Araneta, the town of Silay being the first to raise the Filipino flag. On

November 6, Bacolod, capital of West Negroes, surrendered, and, the following day, the insurgent

leaders, to whom the Spanish governor had just turned over the control of

affairs, established a ‘provisional revolutionary government’. East Negros followed the example of its

sister province, raised the standard of revolt, and organized, toward the end

of the same month, its own ‘revolutionary government’, although that

established at Bacolod, especially after its reconstitution on November 6 into

what was often called the gobierno cantonal de la isla de Negros, made

pretenses at governing the entire island. At all events, the whole island came

under the rule, in one form or another, of the local revolutionists.

“The insurgent

leaders in West Negros, who made up the ‘provisional revolutionary government’,

were, beyond doubt, half-hearted in their

adherence to the Central Government. They flew the Filipino flag, informed

Aguinaldo and Roque Lopez of the establishment of the ‘provisional

revolutionary government ‘, and apparently assumed that their organization,

both before and after the promulgation of the ‘cantonal government’", was

but a part of the Philippine Republic;

yet, at the same time, they acted with extreme independence, going even

as far as sending to General Miller at Iloilo bay on November 12 a communication

inviting protection. While they never

proclaimed a separate republic, as is sometimes wrongly assumed, their relation

to the Central Government up to March, 1899, when Colonel James F. Smith was

sent by General Otis to Bacolod as military governor of Negros, was purely

nominal. Believing as they did in a confederation, rather than a centralized

republic, their loyalty, if it could be so called, to the Filipino Government

has always been open to serious doubt. What has been said regarding West

Negros, however, does not apply with equal force, if at all, to East Negros.

“In the rest of the

Archipelago, the revolutionary movement was reflected with varying strength or

weakness at various times. In the province of Misamis, in northern Mindanao, a ‘provisional

provincial government’ under Jose Roa was established in January, I899. In Surigao, on the north-eastern coast of the

same island, rival factions prevented the organization of a strong government

for the province. The same conditions existed

in Cotabato, which was abandoned by the Spaniards in January, 1899, and in Zamboanga,

wherein the actual outbreak of hostilities against the Spanish troops did not

occur till May. In the island of Palawan, an insurgent party, which had early

taken Puerto Princesa, the capital, and the towns on the northeast coast, set

up some sort of revolutionary government in November or December, 1898, but the

greater part of the island was never brought under its control. The non-Christian

population (i e. pagan and Mohammedan) of Mindanao, and the Moros of the Sulu

islands, as well as most of the pagan mountaineers in northern Luzon, were not

affected by the revolutionary movement, and, throughout the months of revolt in

the rest of the Archipelago, retained the semi-independent status they always

had enjoyed under the Spanish rule.” (Fernandez, 129-139)

Aguinaldo’s success is

the first known achievement of an Asian people toppling down a western power.

But the Spaniards did not go down in defeat before their former subjects

technically because the mixed-up situation gave them a way out of their

predicament by surrendering themselves not to Aguinaldo but to the Americans

after a sham battle and in the process, saving the honor of Spain.

As soon as the republic was formed, Aguinaldo organized the first foreign diplomatic corp and sent emissaries and envoys like Felipe Agoncillo, Galicano Apacible, Mariano Ponce, Jose Sixto Lopez, Heriberto Zarcal, and Jose Alejandrino to the United States, Europe, and Japan to make known to the world about the existence of the newly-established Filipino Republic and obtain its recognition.

The republic's formation is the first-ever sovereign act of the natives of the Philippine

islands previously known as “Indios” - Tagalogs, Ilocanos,

Kapampangans, Bicols, Visayans, etc. – who liberated themselves from the oppressed

status of enslaved people or subjects of the Spanish crown for more than 300

years. They promulgated the first

constitution of the Filipino people, known as the Malolos constitution, arrogating

for themselves the new title of Filipino citizens of the newly-established

republic, the first republic in Asia. This feat is the most outstanding

achievement of the Filipino people, unsurpassed to this day; this period is the

golden age in their history.

However, the

expansionist policy of the McKinley administration and later by Roosevelt

foretold the collapse of the First Philippine Republic.

Thus, on February 4,

1899, the third phase of the Philippine revolution broke out, this time against

the United States, whose policy was that of the annexation of the Philippine

islands. Throwing aside the purported alliance with the Filipinos against Spain,

they withheld recognition of the sovereign rights of the Aguinaldo government. And

this war lasted for more than three years. Here is the summary by an observer:

"...126,500 Americans saw service in the

Philippine Insurrection, the peak strength of the American army at any single

time was 70,000, and this army suffered battle losses of over 4,200 men killed

and over 2,800 wounded. This represented a casualty rate of 5.5 percent, one of

the highest of any war in American history. The financial cost of the war was

over $400 million, a figure 20 times the purchase price paid to Spain. The

insurgents suffered battle losses of 16,000-20,000 killed. In addition, perhaps

200,000 Filipinos died of famine, disease, and other war-related calamities. (Welch,

42)

The tenacity of the Filipinos in keeping the Americans busy for such a long period may be traced to the generous support that the civilian population provided to the Filipino Republican Army. U.S. General Arthur MacArthur took note of this critical aspect of the war in a statement made to an American war correspondent and published in the New York Criterion of June 17, 1889, viz:

"When I first started in against these rebels I believed that Aguinaldo's troops represented only a fraction... I did not like to believe that the whole population of Luzon... was opposed to us, but having come thus far, and having been brought much in contact with both insurgents and amigos, I have been reluctantly compelled to believe that the Filipino masses are loyal to Aguinaldo and the government which he leads.” (Blount, 23-24; Storey and Lichauco, 102)

Why is Aguinaldo being Maligned?

Today, false accusations

stain Aguinaldo’s image, foremost of which are allegations of hunger for power,

complicity in the death of two heroes, and as a Japanese collaborator. Why

would a man of heroic and grandiose achievement be accused, insulted, and

disrespected by the very people he had served?

The root cause of this anomaly may be traced to the archives of the United States Congress in the records of committee hearings giving light to the fact that after American authority was firmly established in the islands in early 1900, and the Aguinaldo-led resistance against the superior American war machine was put down, U.S. military and consular officials of the United States, particularly Admiral Dewey, claimed no alliance with Aguinaldo or promise of independence was ever made to him, viz:

“I never promised ... independence for the Filipinos. I never treated him as an ally, except to make use of him and the soldiers to assist me in my operations against the Spaniards. He never alluded to the word independence in any conversation with me or my officers.” (Malcolm, 121)

No alliance of any kind? Of course, this was a lie. Let us get down to the facts. The Americans were the ones who sought Aguinaldo’s cooperation in fighting the Spaniards in the Philippines. As early as March 1898, the Filipino Junta in Hongkong was elated when Captain Wood, Commander of U.S.S. Petrel, acting on behalf of Commodore Dewey, conferred with Aguinaldo, urging him to return to the Philippines to lead once more the revolution against Spain, on the assurance that Americans would supply him with the necessary arms. Asked about the policy of the United States following the expulsion of the Spaniards from the Philippines, Wood replied that America is a great and rich nation and neither needs nor desires colonies (Agoncillo[Malolos], 98).

Another conference occurred the following month at the residence of a Filipino dentist in Singapore named Dr. Santos, who was pressed by Howard Bray, a long-time resident of the Philippines, to have U.S. Consul Spencer Pratt talk to Aguinaldo who had slipped into the city incognito accompanied by Gregorio del Pilar and Jose Leyva to escape the Arcadio suit in Hong Kong. In this meeting that was also attended by Bray, del Pilar, and Leyva, Consul Pratt told Aguinaldo: “Spain and America have been at war. Now is the time for you to strike. Ally yourselves with America, and you will surely defeat the Spaniards.” (Ibid, 99)

While Aguinaldo was in Singapore, two members of the Hongkong Junta, Messrs. Jose Alejandrino and Andres Garchitorena conferred in French with Admiral Dewey on board the “Olympia” with Lieut. Brumby of the Signal Corp acting as interpreter, and the Admiral was quoted as saying:

“The American people, champion of liberty, will undertake this war with the humanitarian purpose of liberating from the Spanish yoke the people which are under it and to give them independence and liberty, as we have already proclaimed before the whole world. … America is rich under all concepts; it has territories scarcely populated, aside from the fact that our constitution does not permit us to expand territorially outside of America. For these reasons, the Filipinos can be sure of their independence and of the fact that they will not be despoiled of any piece of their territory.” (Alejandrino, 89-90)

A final meeting happened in Hong Kong with U.S. Consul Rounseville Wildman, who proposed to Aguinaldo to establish a dictatorial government to prosecute the war. He was even entrusted by Aguinaldo with the money to purchase 2,000 rifles and 200,000 rounds of ammunition (Agoncillo[Malolos], 102). And, of course, Aguinaldo and his associates were conveyed from Hong Kong to Cavite by U.S. gunboats.

The denial by the U.S. military and Consular officials that there was an alliance with the Filipinos is like saying that Aguinaldo was a liar. To them, his claim that he had a conference with the Admiral on board the “Olympia” upon arrival in Cavite, where he received assurance from the Admiral of support for Philippine independence (Aguinaldo[True Version], 16) was, therefore, a figment of Aguinaldo’s confused mind.

Why did the Americans deny any alliance with Aguinaldo?

Admitting the existence of an alliance would put the Americans in a bad light because it would show that they double-talked and manipulated Aguinaldo into fighting their war and trashed him aside to claim for themselves the victory over the Spaniards. Then when the land forces arrived, they turned against him and suppressed his resistance. This scenario was clearly expressed by Col. James Russell Codman:

"It is an undeniable fact, proved by unquestionable evidence, accessible to any citizen who will take the pains to obtain it, that Aguinaldo's assistance in the war with Spain was solicited by United States officials; that he and his friends were used as allies by the American naval and military commanders; that, until after the capture of Manila, to which they contributed, they were allowed to believe that the independence of the Philippine Islands would be recognized by the American government; and that it was not until after the American forces in the islands had been made strong enough to be able - as was supposed - to conquer the Islanders, that the mask was thrown off. Independence was then refused them, and the purpose of the president to extend the sovereignty of the United States over them by military force was openly proclaimed. That the Filipinos resisted, and that they took up arms against foreign rule, was something that ought to have been expected; for it is exactly what Americans would have done." (Codman, 1)

The fact is, the conquest of the Philippine Islands by the United States was an

act of criminal aggression, using U.S. Pres. McKinley's own words, quoted

from his speech before the U.S. Senate, as he urged for the declaration of war

against Spain, viz: “I speak not of forcible annexation, for that cannot be

thought of. That by our code of morality would be criminal aggression” (Storey

and Lichauco, vi and 74). Using McKinley’s own words, the American

conquest of the Philippines was criminal aggression as expressed by one of his

critics as follows: “… the United States … establish its dominion by

suppressing an indigenous revolution, ignoring a declaration of independence

as a meaningful act of sovereignty, and overthrowing a representatively

convened national assembly.” (Bankoff, 181)

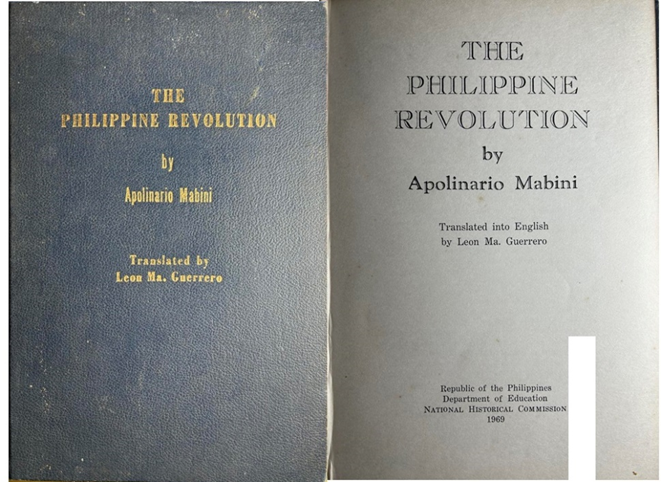

Yes, the Americans came as invaders. Their claim on the islands anchored on

the Treaty of Paris was defective because, according to Mabini, the treaty was

null and void. Spain had lost its right to cede the islands, having been divested

of its claim to sovereignty and authority after its defeat and surrender

(Taylor[IV], 66-69). Any negotiation about the islands' future should have been

between the Americans and the Filipinos. The latter controlled and

administered a significant territory area while the Americans only held the city

of Manila. Therefore, it is safe to declare that excluding the Filipinos from the

treaty conference and barring them from participating in the negotiations was

a deliberate American design to keep them under wraps and unrecognized in

consonance with McKinley’s imperialistic policy.

Maligning Aguinaldo -

American Era

Given the background of Aguinaldo's relationship with the Americans,

presenting him as a liar motivated by selfish interest was necessary. The

Americans would not want to be remembered as the butcher of the Filipinos,

the pillager of their land, and the destroyer of their republic. If Aguinaldo were

looked upon as a liar, more so as a traitor, he would become unworthy of

respect or sympathy by his compatriots. Naturally, everything else associated

with him, especially his patriotic stand against the occupying forces of the

United States, would be taken with skepticism, if not disbelief.

From this American position

proceeded the deliberate act of muddling the historical accounts of the

Filipino-American war and camouflaging the American conquest of the Philippines

as a humanitarian mission consistent with the policy of “benevolent

assimilation,” viz:

(1) The Filipinos were tagged as the initiator of

the war, but the truth is it was the Americans who crossed into Filipino lines

and fired the first shot;

(2) The war was stripped of its rightful importance

and conveniently tucked under the caption, “The Spanish-American War";

(3) The war was not included in the official list of

wars fought by the United States in the 19th or 20th century;

(4) The war was labeled “insurrection,” promoting

the legal claim of the United States under the Treaty of Paris and pre-empting

the sovereign rights of the Aguinaldo government;

(5) Voluminous records and war relics captured

during the conflict were shipped to the United States and stowed away, beyond

the reach of ordinary Filipinos, except to those historians given access by the

U.S. military;

(6) The Sedition Act that was passed and was

effective for 12 years criminalized the

display of the Filipino flag, any public gathering, or speech or writing that

had a patriotic theme;

(7) A public school system was established to teach American

history, culture, arts, songs, literature, and heroes that molded a new

Filipino who is detached from his inherent intellect and knowledge and made him

love America more than his own country; and,

(8) Aguinaldo was branded a traitor to his people

for agreeing to the Biak-na-Bato peace pact and for taking the oath of

allegiance to the United States, disregarding the fact that more than a

thousand Filipino prisoners would be indefinitely jailed if he did not take

the oath.

Among the early

publications that pictured Aguinaldo negatively is the one by Murat Halstead

(1829-1908), which, just by reading the title, gives the impression that the

content is part of a grand conspiracy to besmirch the image of Aguinaldo. The

title reads: “The politics of the Philippines: Aguinaldo a traitor to the

Filipinos and a conspirator against the United States; the record of his

transformation from a beggar to a tyrant.” (Halstead, 1)

Aguinaldo himself expressed his disenchantment at one time when he

said:

"I have been loyal to America and the Americans. I have at

all times acted upon their advice and complied with their desires, yet in their

daily journals, they endeavor to humiliate me before my people. They call me

thief, renegade, traitor, for no reason. I have done them no harm; I have

assisted them to their ends, and they now consider me their enemy. Why am I

called a renegade, traitor, thief?" (Sheridan, 90)

Paradoxically, today, we see a memorial in honor of McKinley. Why

should the Filipinos dignify this hypocrite by naming after him a major

thoroughfare that runs through the most expensive pieces of real estate in the

country, terminating at the beautiful park in the plush commercial center in

Taguig? Either Filipinos are gullible, or they are ignorant of their history.

Maligning Aguinaldo - Quezon era

Enter Manuel L.

Quezon. According to an article in the U.P. Los Banos Journal, Quezon

served in the Batallion Leales Voluntarios de Manila of the Spanish army

during the revolution against Spain (Javar, 5); his father, Lucio, similarly

took the side of the Spaniards and helped the beleaguered Spanish soldiers

holed up in the church of Baler, was captured and killed by the

revolutionaries (Ibid, 10).

Like several officers

and soldiers of the Spanish army, Quezon joined the Filipino Republican Army

after Spain surrendered. His rise in the Philippine political scene was

phenomenal. With the collapse of the First Philippine Republic, he concentrated

on politics and became friends with Americans like Harry Brandholtz,

James G. Harbord, and General Douglas MacArthur. It was not implausible that he

would cross paths with Aguinaldo, who was still considered the “El Caudillo”

and hero for having led the revolution against Spain and the resistance against

the Americans.

Here is how Quezon was

viewed as a politician:

". . . Quezon was ingratiating and

charismatic, a brilliant orator and a consummate politician. He was audacious,

resourceful, unencumbered by integrity, and capable of shrewdly using his

political strengths to mold public opinion. His assessments of those with whom

he dealt were unerring. He manipulated where he could – Filipinos and Americans

alike – and used the electoral process to bludgeon those Filipinos who

challenged him. He equated political opposition with enmity and was ruthless in

dealing with influential Filipinos who were loyal to rival leadership or to

abstract ideas that incurred his ire. These qualities were moderated only by

the transfer to himself of the loyalty of Filipinos buffeted by his

combativeness or their withdrawal from the arena of insular

politics." (Golay, 166)

Quezon and Aguinaldo did

not see eye to eye. As soon as Quezon came home from his mission to the

United States and reported that he was also considering two alternatives to

independence that were not necessarily full, immediate, and absolute as

originally agreed upon by the independence committee, Aguinaldo accused him of

being a traitor to the Filipino cause. (Golay,

297).

Did Quezon want

independence? Here is the answer of a critic:

"The answer is

no... Quezon wanted to become the chief executive of a government ran by

Filipinos and protected by a benevolent American people in exchange for which

certain rights and privileges would be granted to the United States and

Americans." (Onorato, 229)

This kind of arrangement

would become a reality in the form of military bases and parity rights

agreements that were signed after 1946.

And in Quezon’s conflict with

Governor Leonard Wood, Aguinaldo took the opposite side. Whether these personal

differences influenced a belligerent response from Quezon is unclear now. But

the involvement of certain personalities associated with Quezon in incidents

that dragged Aguinaldo’s name into controversies would lead to the conclusion

that the active hand of Quezon was strongly evident. These incidents are as

follows:

1. As early as

1917, Guillermo Masangkay, an associate of Supremo of the Katipunan, Andres

Bonifacio, and later identified with Quezon, led a party to locate and exhume

the remains of the Supremo in Cavite and had these identified by Bonifacio’s

sister and proclaimed authentic by the National Museum Director, Epifanio delos

Santos, (Santos[Katipunan], 178-183). The alleged bones were paraded around the

city of Manila and placed in a beautiful glassed container, and displayed in

the National Museum. This demonstration elicited sympathy for Bonifacio and

anger at those suspected to be responsible, and the finger pointed at Aguinaldo

for his alleged role and complicity.

2. Pantaleon Garcia, a former General in Aguinaldo’s army,

who had become the Sargeant-at-arms of the Philippine Senate of which Quezon

was president, issued a statement in 1930 to the effect that

Aguinaldo allegedly instructed him to kill General Antonio Luna, which he was

unable to do because of sickness at the time. (Garcia[Pantaleon], 22)

3.

A certain Antonio Bautista, who used to be the campaign

manager of Aguinaldo in Bulacan, abruptly moved over to the Quezon camp. He allegedly orchestrated the circulation of

a story billed as "pagluluksa sa

Malolos" (mourning in

Malolos), in which the townspeople of the town were said to

have hung black drapes and closed their windows when Aguinaldo arrived

(Veneracion, 249; Constantino, 20-21).

4.

Aguinaldo was also subjected to harassment economically

and financially. The annual pension of P12,000 granted to him under Philippine

Legislature Act No. 2922, which was approved on March 24, 1920, was stopped by

the express repeal of Commonwealth Act No. 288 under the Quezon administration

in 1939. The pension was only restored

in 1957 through RA 1808.

5. And last but not least, Eulogio Rodriguez, then the Secretary of Agriculture and Commerce in the cabinet of Quezon, summarily stripped Aguinaldo of all but 344 hectares of landholdings on the pretext that he failed to pay the installments due on the loan he had obtained from the government for the acquisition of the friar estate in Cavite. (Ara, 168-169)

So, for those with the

critical eye, they will not fail to notice that three major thoroughfares in

Quezon City that intersect each other are named after Manuel L. Quezon (the Quezon

Avenue), Epifanio Delos Santos (the EDSA), and Eulogio Rodriguez (the E.

Rodriguez Avenue). Is this a pure coincidence, or is it to immortalize the

significant roles played together by the three personalities in history and not

necessarily their contribution to the country?

Under the

atmosphere at the time, it would not be difficult to add to the “sins” of

Aguinaldo the alleged sell-out of the revolution at Biak-na-Bato, the alleged

malversation of the peace agreement money, his alleged complicity in the death

of Andres Bonifacio and General Antonio Luna, and the blame for the failure of

the revolution. But true or not, the desired result was accomplished -

Aguinaldo was transformed from hero to villain. Therefore, it seemed logical to

conclude that Aguinaldo’s defeat in the 1935 election for the presidency of the

Commonwealth was not really because Quezon was more popular than Aguinaldo but

rather the result of the massive campaign to malign Aguinaldo in the eyes of very people he had endeavored to serve.

Maligning Aguinaldo -

Japanese Occupation

The Second World War added to the denigration of the public image of Aguinaldo. When the

Japanese-sponsored 2nd Philippine Republic was inaugurated with Jose P. Laurel

as president, Aguinaldo considered it the realization of his dream. He believed

the Japanese were more sympathetic to the Filipino aspirations for freedom

because, in less than three years, a Filipino Republic was established, while

the Americans required a ten-year Commonwealth period to determine if absolute

independence would be granted. Perhaps, this belief was anchored on his

positive experience with the Japanese, who sent advisers and armaments to help

the Filipinos during the Filipino-American war. Accordingly, Aguinaldo actively

assisted in efforts to end the Pacific war in the Philippines as soon as

possible in the hope that peace would give the Second Philippine Republic a

chance to succeed. But his efforts were construed differently - he was accused

of aiding the enemy as a Japanese collaborator, a label that continues to haunt

his memory to this day.

Maligning Aguinaldo - by

Leftist Elements

The advent of

Marxist-Leninist ideology in the Philippines added to the vilification of

Aguinaldo’s image. The ideology manifested itself in the early 1900s

and propagated after World War II, taking root among nationalist-leaning

historians, students, and academicians, especially in government-funded

universities. To bolster their leftist agenda, i.e., create a revolutionary situation leading

towards the overthrow of the existing bourgeois establishment, the advocates

took advantage of the anti-Aguinaldo propaganda during the American era.

Bonifacio was hijacked to serve as the vital component of the

configuration. He was made to represent the rallying symbol of their

advocacy because, in the structure of their concept, Bonifacio personified the

masses, Aguinaldo, the elite, and therefore, the enemy. The two heroes

were pitted against each other as a way of bringing back to life the leadership

conflict of the revolution. This conflict was made to represent the

supposed contemporary and continuing class struggle in the Philippines.

And to make the complex Communist ideology easier for the youthful minds to absorb,

the supposed class struggle was paralleled to the Bonifacio-Aguinaldo feud of

old.

In the process, the revolution of 1896 against Spain led by

Bonifacio became the revolution of the leftist, even if the ideology was never

a factor at that time. By claiming that the

revolution was that of the masses, it is effectively juxtapositioned to the

present because, by their definition, the leftists are the masses. So, as

far as the leftists are concerned, to be a disciple of Marx, Lenin, or Mao is

an act of patriotism, and therefore to

rebel against the established order is justified, in the same manner, that

Bonifacio’s revolution was. Of course, this is a pure and straightforward

web of insidious machination and propaganda.

But apparently, the strategy works. The theoretical social

conflict of masses versus the elite that used to be an abstraction in the minds

of intellectuals has now become understandable to the neophytes. This explains

why the incessant noise in social media about Aguinaldo being “hungry for power,”

a “traitor,” “a murderer,” and a “coward” is coming from the younger generation

who hardly knows the history of their country and Aguinaldo’s contribution to

nationhood.

Conclusion

In the final analysis,

Aguinaldo’s legacies – the national flag, the national anthem, but more

importantly, the national aspiration to be free and independent handed down by

the architects of the First Philippine Republic, will endure forever, and so

will the memory of Aguinaldo. And today, the image of Aguinaldo as a patriot

and hero is becoming strongly evident, bolstered by the exposure of historical

facts clandestinely kept under wraps in the past that are now accessible through

the internet.

In homage to the man,

here is Aguinaldo’s role in history, according to Gabriel F. Fabella (Garcia[Mauro], 26-27):

(1) Aguinaldo was the first man to make the world

conscious of the existence of the Philippines by leading two revolutions

against Spain and a war of defense of their newly established republic against

the United States. As a consequence, he is the first Filipino whose name

appears in the world encyclopedias.

(2) He helped to weld the Filipinos into a nation

through deeds rather than by pen or words;

(3) He was the first man to demonstrate that a

Filipino is capable of running an orderly government of his own making;

(4) He set an example of honesty, integrity, and

incorruptibility in the government service; left happy memories of the First

and Second Republics of the Philippines, and finally,

(5) He bequeathed permanent legacies to our people:

(a) Philippine independence, (b) A Filipino flag, and (c) A national anthem.

2.jpg)

.jpg)

%20-%20public%20domain%20(cropped).jpg)